Book Notes

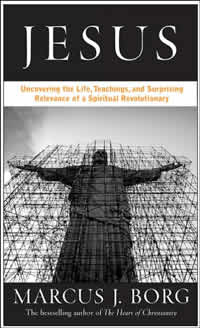

Marcus Borg,

Jesus; Uncovering the Life, Teachings, and Relevance of a Religious Revolutionary

(San Francisco: Harper, 2006), 343pp.

Marcus Borg,

Jesus; Uncovering the Life, Teachings, and Relevance of a Religious Revolutionary

(San Francisco: Harper, 2006), 343pp.

Marcus Borg, professor at Oregon State University, is one of a very few prominent New Testament scholars who writes for the everyday Christian, who declares his passion for a vibrant faith, who shares personally from his own experience, who is unapologetic but irenic in presenting his views, and on top of it all an excellent writer. Although I have my disagreements with him at any number of places, I have previously enjoyed his other popular books, Meeting Jesus Again for the First Time (1994), Reading the Bible Again for the First Time (2001), and The Heart of Christianity (2003). If you have read these previous books, you won't learn much new by reading Jesus . The book began as a modest revision of Jesus: A New Vision (1987), but has been marketed as a new book because the revisions were so extensive.

Borg promotes what he repeatedly and irritatingly calls "mainstream scholarship," as if others who are not part of his club are best disregarded. He does a good job of incorporating that movement's strengths, and at times admits where and why some issues are complex, opinions divided, and the choices more like a subjective art. But he ignores the corrosive tendencies of extreme historical criticism, along with the best evangelical scholarship that has interacted with it (unlike in his book co-authored with NT Wright, The Meaning of Jesus; Two Visions , 2000). What he calls the "emerging Christianity" of mainline denominations positions itself in clear contrast to conservative evangelicalism. The latter, Borg believes, is wrongly preoccupied with biblical literalism, the afterlife, and believing right doctrines. Emerging Christianity, he argues, is "way-centered" instead of belief-centered. Whereas evangelicalism represents a "defensive rejection" of the Enlightenment, his vision attempts a "discerning integration."

Central to Borg's method is his effort to distinguish between "history remembered" or "pre-Easter memory," in the sense of events in the life of Jesus that really happened, and "post-Easter metaphor," in the sense of the constructions of later Christians. The former constitutes the real voice of Jesus, the latter the voice of the community. Implicit in his distinction is the insinuation that the "voice of Jesus" enjoys an epistemological privilege over the "voice of the community." Many, of course, have observed this wedge driven between the "Jesus of history" and the "Christ of faith." Borg tries mightily to resist that tension: "A historical-metaphorical way of reading the gospels does not see them as fantasy or exaggeration or deception, but as the testimony and witness and convictions of Jesus's followers" (p. 49). Or again, "The metaphorical meaning of language is its more-than-literal, more-than-factual meaning. Metaphor refers to the surplus of meaning that language can carry." Fair enough. But Borg never addresses what a believer ought to do if, as would be the case with him, she thinks that the later believers were simply wrong when they claimed that Jesus was God in the flesh and that the Easter tomb was empty. Borg rejects the historicity of both beliefs; the best he can say is that either way it does not matter (p. 279, 287). That's hardly a satisfying answer. It does matter, according to Paul (1 Corinthians 15:12–19).

Borg shines when he expounds how Jesus reveals the character or nature of God (compassion), and his passion or will for the world (justice). I especially appreciated his exposition of the centrality of the kingdom of God, and his demonstration of how God's kingdom is both deeply personal and explicitly political. If Jesus is Lord, and Borg passionately confesses that He is, then Caesar and imperial powers are not lord. In his subversive wisdom and teaching Jesus challenges all such idolatrous principalities, powers, and authorities. Praying the Lord's prayer for this kingdom to come is, then, a way of confessing what earth would be like if God and not the state powers were in charge. And that is truly good news.