Book Notes

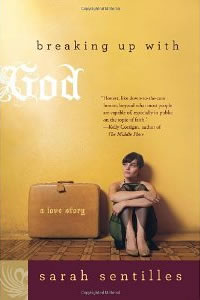

Sarah Sentilles, Breaking Up With God; A Love Story (New York: HarperCollins, 2011), 244pp.

Sarah Sentilles, Breaking Up With God; A Love Story (New York: HarperCollins, 2011), 244pp.

Sarah Sentilles was in the middle of an ordination process to become an Episcopal priest, and a doctoral student in theology at Harvard, when at the age of thirty-four she left her Christian faith for good. It was a long time coming. In this candid memoir she explains how and why she made that choice.

There's nothing remarkable about her loss of faith — critical inquiry led to the accumulation of honest questions about important issues. If God is male, then isn't the male God (Mary Daly), and don't women lose their power to write their own stories? Children die of cancer and the elderly lose their identity to Alzheimer's. The church as a flawed institution, which Sentilles engaged for most of her life, comes off badly in her book. A two-year stint with Teach for America in urban Los Angeles, after a privileged upbringing and college at Yale, provoked disturbing questions about social justice. A major theme in her journey is her search for personal wholeness beyond her eating disorder, years of therapy, poor choices about bad men, and learning self-acceptance.

Sentilles developed a "canyon" between her personal piety and her critical inquiry as a doctoral student at Harvard, "between the God I was in love with and the God I was studying" (108). She could never bridge the gap between "my intellectual version of God and my personal version of God" (140). There was another disconnect between "the theology I studied in school and the theology being practiced in the pews and preached from the pulpit by the priests on staff [which] was enormous… everything I took for granted… was absent, even heretical" (152–153).

On Sundays Sentilles no longer goes to church. She goes to the farmers' market: "this is a kind of faith for me" (215). After all the important questions that she's rightly raised, "too many terrible things done in his name. Too much suffering in the world. Too much violence. Too many disasters" (214), this is where she leaves us. At least this feeble conclusion makes her pause: "Really? You're going to end your book about God with the farmers' market? Yes. I'm going to end my book about God with the farmers' market" (216, italics are hers). Buying farm fresh eggs and eating vegetarian is noble, but they're a poor follow-on for her rigorous inquiry about faith and doubt. I look forward to her next book about faith after the farmers' market.