Book Notes

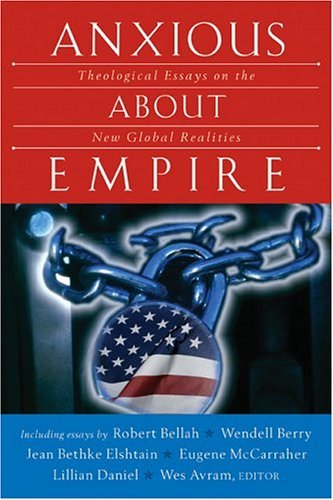

Wes Avram, editor, Anxious About Empire; Theological Essays on the New Global Realities (Grand Rapids: Brazos Press, 2004), 218pp.

Wes Avram, editor, Anxious About Empire; Theological Essays on the New Global Realities (Grand Rapids: Brazos Press, 2004), 218pp.

The 2004 presidential election revealed, among other things, some very deep fault lines that run throughout American Christendom. Many of us had conversations with fellow believers that left us incredulous at how our conversation partner could possibly believe whatever was the "opposite" side. Wes Avram, a professor at Yale Divinity School, has collected thirteen essays by scholars and pastors that examine the relationship of the Christian church to America as the sole super power today. But for two or three exceptions, all of the essays express consternation at the extent to which Christians have wrapped the Gospel in the flag, and the state has co-opted Christian rhetoric to justify its imperial aspirations.

On September 17, 2002, the White House published The National Security Strategy of the United States of America, a document about twenty-five pages long, with a three page preface by President George W. Bush. Avram has included this as an appendix. All of the authors were asked to respond to this so-called Bush Doctrine as a point of departure for their reflections. American hegemony is a given today, in economics, politics, culture and certainly the military. Part of this was by our own designs, but as Robert Bellah reminds us, in other ways it was unintentional. Whatever the reasons, and whether we think it is justified or not, it is clear that much of the world today is anxious about America, angry at us, and very much against us. It would appear that our aspirations to empire, our insistence that our political and economic way of life are not only the best but must be followed by everyone else, are not only undesirable but even unsustainable in the long run. On the other hand, there are very real crises in the world that demand our active projection of power—genocide, failed states, vicious terrorism, global HIV-AIDS, and the like. At times there results a sort of national schizophrenia—we insist on opening global markets for our own economic good, but we also refuse to participate in many if not most international treaties. We speak of fostering universal rights like economic and political freedoms, but then act with undisguised self-interest.

I especially appreciated the four chapters in this book that were written by articulate pastors who had given considerable thought, rooted in everyday parish experiences, about how to guide the ordinary believer in the pew to think about these many and complex questions. One particular question was raised for me: if a Christian is called always to act with deferential regard for the other, and a nation-state is by definition always called to act out of self-interest, it would seem that Christian identity and national identity are at root fundamentally at odds with one another.