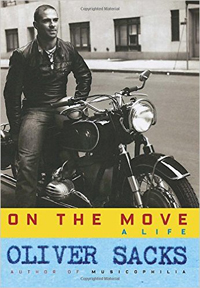

Oliver Sacks, On the Move: A Life (New York: Knopf, 2015), 416pp.

A review by physicist Brad Keister. Brad and his wife Katie worship at Washington Community Fellowship, on Capitol Hill in Washington, DC.

On the Move is the memoir of Oliver Sacks, published just a few months before his death this year from cancer at the age of 82. Sacks, a neurologist, is known for his writings of case studies of his patients, including Awakenings (adapted as a film in 1990 with Robin Williams and Robert De Niro), The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, and Musicophila: Tales of Music and the Brain.

On the Move is the memoir of Oliver Sacks, published just a few months before his death this year from cancer at the age of 82. Sacks, a neurologist, is known for his writings of case studies of his patients, including Awakenings (adapted as a film in 1990 with Robin Williams and Robert De Niro), The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, and Musicophila: Tales of Music and the Brain.

Sacks wrote this memoir in a similar vein, illustrating his perspectives by means of people he met along his lifelong journey. Born in England, Sacks received his medical degree at Oxford and then moved to the United States, where he held positions in Los Angeles and San Francisco before moving to New York, where he spent most of his professional life. His journey was punctuated by interludes that we don’t normally associate with that of a high-functioning professional, including a summer at a kibbutz in Israel, a stay in Venice Beach, California, where he set a weightlifting record, and a cross-country trip on one of his beloved motorcycles. True to the memoir’s title, Sacks considered himself as on the move even when physically in one place.

Sacks emerges from this memoir as very much a loner. Many of his published works were not appreciated at the time, and several were published only because of the advocacy of a few individuals who clearly saw their great merit. He also did not always fit in to his professional environment. In one instance, while on the staff of Beth Abraham Hospital in New York, Sacks was asked to vacate an apartment that was reserved for him as the on-call physician. When he questioned the request, the hospital director both removed him from the apartment and terminated his appointment.

Sacks also writes of the effect of his extreme shyness on his relationships with others. In that vein, he describes living with his homosexuality, having addressed it in full less than ten years before his death. In his work and his writings, Sacks went beyond a view of the mind that had only two states — functioning or failing — to the perspective that our varied neurological makeups speak to the very core of who we are. In so doing, he challenged our notions of what constitutes normal or right about others and about ourselves.