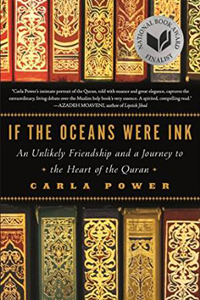

Carla Power, If the Oceans Were Ink; An Unlikely Friendship and a Journey to the Heart of the Quran (New York: Henry Holt, 2015), 336pp.

Carla Power, If the Oceans Were Ink; An Unlikely Friendship and a Journey to the Heart of the Quran (New York: Henry Holt, 2015), 336pp.

We hear a lot today about the clash of civilizations between the Muslim east and the Christian west. George Bush divided the world into binary opposites with his insistence that "either you're for us or against us." Carla Power moves us beyond such crude stereotypes and convenient generalizations. Her book about spending a year studying the Quran with her friend Sheikh Mohammad Akram Nadwi (b. 1964) of Oxford was a finalist for the 2015 National Book Award in non-fiction.

Power calls herself a "skeptical" feminist and "dutiful little secularist." Her Jewish father and Quaker mother were both non-practicing. Thanks to her father's peripatetic ways, she grew up in Tehran, Kabul, Delhi, and Cairo, although she's quick to admit that her knowledge of Islam was always one held at arm's length. That is, until she studied with the Oxford imam and scholar Nadwi, a friend of twenty years.

The Sunni Nadwi defies labels. He was born in India and made his way to Oxford. Fluent in several languages, he's published twenty-five books. He's also completed a biographical dictionary in 53 volumes that identifies over 8,000 women scholars of hadith (a collection of traditions about the words and deeds of the Prophet Mohammad). He's complicated enough to disappoint both progressives and traditionalists.

When "properly read," Nadwi insists, the Quran "reveals a just and humane faith." And so a major theme of his work has been a close reading of the original sources to excavate the spiritual essence of the faith. He laments the cultural accretions that have ossified true faith, politics that supplant genuine piety, and ancient customs that have no support in the Quran. For him, "islam" (small i) is more of a verb than a noun. What matters most is taqwa or God-consciousness. We must always respect human conscience; there can never be compulsion in true religion. In his view, to take one example, what restricts women is patriarchal cultures and not Islam's tenets.

But Nadwi is hardly a liberal. He accepts polygamy and traditional domestic roles for women (he has six daughters). He believes in a literal paradise for believers and hell for unbelievers (like Power, he admits). He's opposed to homosexuality. Veiling is fine, despite all sorts of cultural complexities and nuances.

At times Power's narrative borders on hagiography. She's captivated by Nadwi's combination of erudition, piety, and kindness. In the end, she admits that theirs was a one-way conversation rather than a dialogue: "I wanted him to take a step toward my worldview, as I'd done toward his." That was never going to happen.

Still, Power earns high marks for being open to an "other." It's a model we all do well to follow, each in our own way and in our own little world. She writes, "if understanding difference is among my own key values, it is also a Quranic one. Only through diversity, says the Quran, can you truly learn the shape and heft of your own humanity: 'O humankind, We created you from a male and female, / and We made you races and tribes / for you to get to know each other.' (49.13)."