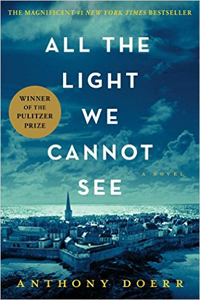

Anthony Doerr, All the Light We Cannot See (New York: Scribner, 2014), 531 pp.

Anthony Doerr, All the Light We Cannot See (New York: Scribner, 2014), 531 pp.

Anthony Doerr’s Pulitzer Prize winning novel, All the Light We Cannot See, interweaves the stories of two children, a blind French girl and an orphaned German boy, whose paths collide in occupied France during World War II. Marie-Laure, a bright, inquisitive, and resourceful girl, lives with her widowed father in Paris, where he works as master locksmith of the Museum of Natural History. When Marie-Laure goes blind at the age of six, her father builds her a perfect miniature of the city, so that she can memorize and navigate her neighborhood by touch. Marie-Laure is twelve when the Nazis occupy Paris, forcing her father and her to flee to the walled citadel of Saint-Malo, carrying with them the Museum’s most valuable, most storied, and potentially most dangerous treasure – a blue diamond called the Sea of Flames. There, haunted by demons both imagined and real, Marie-Laure has to endure the pain and loss of war, choosing again and again between fortitude and despair.

Meanwhile, in an impoverished coal-mining town in Germany, Werner grows up in an orphanage, listening longingly to radio broadcasts, and dreading his future in the mines. When he turns out to be an engineering prodigy, he future shifts, landing him in an elite but brutal academy for Hitler Youth. There, he is schooled simultaneously in the technology he loves, and the Fascist ideology he can’t muster enough courage to resist. Eventually, he is sent out to track the resistance, and forced to confront the horrible human cost of his work. It’s at the tail end of this journey that his story collides with Marie-Laure’s.

Written mostly in the present tense, in short, gorgeously wrought chapters rich in detail and metaphor, Doerr’s novel is at once lyrical and suspenseful. Marie-Laure’s blindness is convincingly portrayed, as is the political, social, and cultural devastations of war. Doerr’s pacing is so skillful that readers will be tempted to read fast toward the novel’s satisfying climax -- but that would be a mistake. Line by line and chapter by chapter, Doerr’s rich, textured prose deserves to be savored. Like the elaborate puzzle boxes Marie-Laure’s father handcrafts for her birthdays, All the Light We Cannot See best yields its treasures slowly, one tiny lock and key at a time.