David McCullough, The Wright Brothers (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2015), 320pp.

David McCullough, The Wright Brothers (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2015), 320pp.

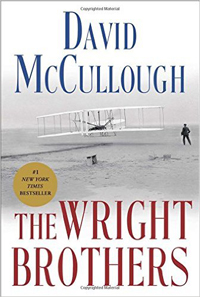

On Thursday December 17, 1903, at 10:35 in the morning, in the presence of five men, Orville Wright flew for 12 seconds and 120 feet above the beaches of Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. It was one of the most important pivot points in all of human history. The "Flyer" that he and his brother Wilbur had built had a four cylinder motor that produced eight horsepower, a one gallon fuel tank, two propellers that were eight-and-a-half feet in diameter, and weighed about 600 pounds. The moment was captured in one of the most iconic photographs ever taken, which picture graces the cover of the book.

After more trial and error, more and better flights followed — 105 flights in 1904. In the summer of 1905, they routinely flew 24 miles in 38 minutes, taking off and landing in the same spot. It seems strange today in our media-saturated culture where information travels around the world in seconds, but it wasn't until 1908 in France that the first real media attention and full scale public demonstrations occurred, by which time they were flying two hours at a time across 77 miles at 40 miles per hour, before enthusiastic crowds of thousands and the kings of England, Spain, and Italy.

The master historian David McCullough has won two Pulitzer Prizes, two National Book Awards, and a Presidential Medal of Freedom for his previous work. This book shows why. It's brisk enough to be a page-turner that doesn't bog down in details, but comprehensive enough to tell the whole story, based upon diaries, notebooks, and over a thousand letters. He's especially interested in the special closeness of the entire Wright family, the unique role that their sister Katharine played (the only one in the family to go to college), and the genuine rectitude and modesty of the inseparable bachelor brothers who began life as bike mechanics in Dayton, Ohio.