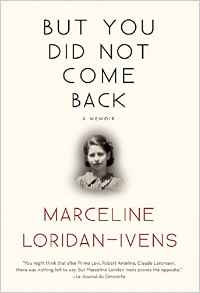

Marceline Loridan-Ivens, But You Did Not Come Back (New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2016), 100pp.

Marceline Loridan-Ivens, But You Did Not Come Back (New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2016), 100pp.

Marceline Loridan-Ivens (b. 1928) was fifteen when she and her father were arrested and deported to the Nazi death camps — she to Birkenau, and he to Auschwitz, just three kilometers away. Before they were deported, at the Drancy internment camp, she told her father, "We'll work over there and we'll see each other on Sundays." He replied, "You might come back, because you're young, but I will not come back." His grim prophecy was correct.

Despite their separation, her father managed to smuggle a note to her: "a stained little scrap of paper, almost rectangular, torn on one end. I can see your writing, slanted to the right, and four or five sentences that I can no longer remember. I'm sure of one line, the first: 'My darling little girl,' and the last line too, your signature, 'Shloïme'." This holocaust memoir, originally published in France (where it's been a best seller), is her own letter written to her father.

Loridan-Ivens was tattooed with the number 78750 on her left arm. She lived in prison block 27B, in the row closest to the crematorium, where she could see children walking to the gas chambers. She helped to build the rail line that led directly to the furnaces where those children were taken, dig the ditches for the mass graves, and sort through the mountains of clothes. "I served death. I'd been its hauler."

The liberation of the camps and eventual repatriation in France brought little peace. Two of her siblings committed suicide, and she herself tried to take her own life twice. Loridan-Ivens is one of 160 people still alive out of the 2,500 who survived, from the 76,500 French Jews who were sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau. "If you only knew, all of you, how the camp remains permanently within us. It remains in all our minds, and will until we die."