For Sunday July 25, 2021

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

2nd Samuel 11:1-15

Psalm 14

Ephesians 3:14-21

John 6:1-21

Early last winter, my next door neighbor and I happened to step onto our back patios at the same time. I was taking out recycling, and she was tending to her plants. We pulled our masks over our faces, and chatted for a moment by the fence. We bemoaned the long, terrible isolation of quarantine. We noted the fact that neither of our families would get to see our loved ones over the holidays. We wondered when we’d ever have friends inside our homes again. When we’d gather at restaurants, or sit around our own dinner tables with people outside our immediate “pods.”

And then we paused and looked at each other hopefully. Was there any way our two families could share a meal safely? Wouldn’t it be so fun, so wonderful, so life-giving if we could?

After much discussion, we decided to do it. We chose a night, and agreed on all the rules. We’d open the gate between our patios, and sit outside, distanced, at two tables, wearing masks whenever we weren’t actively eating. Each family would bring their own plates and cups and cutlery. We wouldn’t share serving utensils. But we’d still be together. Plan a menu. Share food and wine. Talk, laugh, eat, drink, gather.

When I look back now on the long, fear-filled winter of 2020, that November meal shines out like a beacon. I remember with such fondness the effort our two families put in to make the evening festive. The way we scrubbed down our patio furniture, and pulled out our fancy linens and dishes. The candles we lit and the wine we opened. The favorite dishes we prepared for each other, and the way we lingered at our tables late into the evening, long after the sun went down and the night grew cold.

|

This week, our lectionary reading centers around a shared meal. Specifically, it centers around Jesus's multiplication of loaves and fish to feed a crowd of five thousand. This is the only Jesus story that appears six times across the four gospels. Clearly, the event meant a lot to the early church. But I wonder if it might mean a lot to us this year, too, after the long isolation we’ve just endured.

I know that there are any number of conversations or even debates to be had about what exactly happened with that crowd and that little boy’s lunch two thousand years ago. Did Jesus really break the laws of science as we know them, and multiply those loaves and fish? Or was the actual miracle the opening of hearts and the channeling of generosity, such that five thousand people decided, as a result of their encounter with Jesus, to share their precious food with each other?

We can’t know. For my part, I’m fine with believing that Jesus did something supernatural that human beings can’t explain. If the God who created the cosmos and resurrected the Christ caused the content of one child’s lunchbox to become a feast for thousands, I can live with that.

But what strikes me about the story this year is something slightly different than the miracle of the food itself. It’s the miracle of gathering.

As John describes the scene, Jesus crosses the Sea of Galilee, and takes his disciples up a mountain. Immediately he notices a large crowd following them — a crowd filled with hope, need, want, and hunger. Now here’s the interesting part: Jesus’s first thought when he sees the throngs of people approaching is, “How might we create conditions where they can remain together? Where they can have their needs met in community? How can we gather them, and help them to receive nourishment in relationship to one another?”

We know from the other Gospel accounts that the disciples don’t share this wavelength with Jesus. In Mark’s version, they object to their teacher’s desire, and say, “This is a deserted place, and the hour is now very late; send them away so that they may go into the surrounding country and villages and buy something for themselves to eat.” In other words, the disciples’ instinct is to scatter the people. To send them off to fend for themselves. To resist the work, the burden, and the responsibility of meeting their needs in community.

|

Maybe, after the past year, we are in an especially good position to appreciate Jesus’s vision. We, too, have been scattered. We have known the loneliness of the empty table, the unused guest room, the locked up church building, the fast from Eucharist. We have discovered anew how sacred and life-giving it is to gather, and how much we ache when we’re denied the means to do so. We’ve experienced in urgent ways how much our humanity depends on proximity. On eating together, and finding nourishment together. I wish I knew the original source of this wonderful phrase, but I have heard it said more than once that “Christianity is the eatingest religion in the world.” Indeed.

Consider how many of the Jesus stories we love center around meals, feasts, and dinner tables. The gospels are full of references to Jesus eating and drinking with others. He multiplies wine in Cana to keep a party going longer. The religious leaders of his day accuse him of gluttony because he practices table fellowship with sinners. He accepts the dinner invitation of Simon, a Pharisee, and invites himself to the home of Zacchaeus, a hated tax collector. His last act of love for his disciples before his death is to gather them around a table, and feed them bread. His own body.

When Jesus feeds the five thousand, he does more than fill their stomachs. He encourages hungry, needy, weary people to sit down together, to notice and attend to each other, to take pleasure not only in the possibility of their own fullness, but in the fullness of the whole. The point is not to hoard, scheme, conserve, or quantify. The point is to enjoy abundance in community. To learn that in God’s kingdom, there is enough. Not just enough for one, but for many.

Again: not just enough for me, or for my family, or for my “pod,” “people,” or “tribe,” but enough for absolutely everyone. With more to spare.

When Jesus feeds the multitudes in one place, at one time, he acknowledges that we are physical and communal beings, with physical and communal needs. We're not airy, disconnected spirits; we have bodies — both individual and collective — and those bodies themselves are gifts from God. Gifts worthy of honor and care.

|

Whatever the miracle is, Jesus is able to perform it precisely because he takes these basic human needs so seriously. When his disciples look at the crowds, they see only their own insufficiency. Their own scant resources. The impossibility of the situation. But Jesus allows himself to see genuine need, and he allows that need to hit him squarely in his own gut. In the face of the crowd’s deep hunger, despair and apathy are not options; someone has to act. Someone has to feed. Someone has to gather.

Maybe it’s only when we get in touch with our own deepest needs — for nourishment, for companionship, for proximity, for intimacy — that we can extend a generous table to others. Maybe we need to be felled by our own hungers before we can turn abstract compassion into life-saving action.

“The crowds ate and were satisfied.” Is this because they eat in the presence of Jesus? What would that be like? To invite him to our tables? To let him watch and partake as we gather together? To welcome the incarnate Jesus into the intimate realm of our bodily hungers? Our social hungers? Where might such brave communion lead?

In the end, Jesus's feeding miracles are his self-revelations. He gives bread because he is Bread. He makes possible the gathering of the body so that we might become his body, the church. May our gatherings honor his generous legacy.

Debie Thomas: debie.thomas1@gmail.com

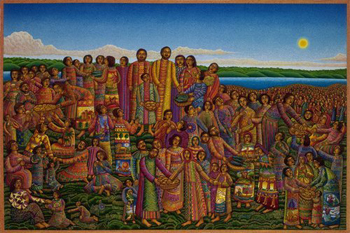

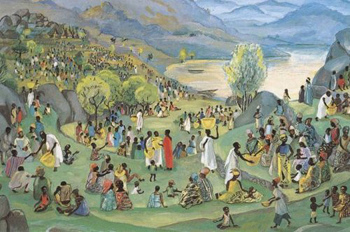

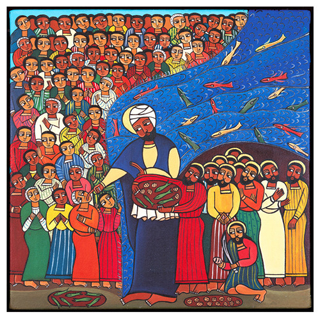

Image credits: (1–3) Global Christian Worship.