God at Play

By Debie Thomas

"'Oh children,' said the Lion, "'I feel my strength coming back to me. Oh children, catch me if you can!'"

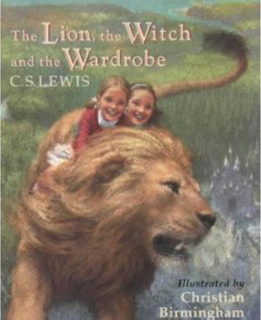

The speaker is Aslan, the majestic lion and Christ-figure of C.S Lewis' classic children's novel, The Lion, The Witch, and the Wardrobe. The scene follows Aslan's sacrificial death and resurrection — witnessed by two children, Lucy and Susan — and continues thus:

"A mad chase began. Round and round the hilltop he led them, now hopelessly out of their reach, now letting them almost catch his tail, now diving between them, now tossing them in the air with his huge and beautifully velveted paws and catching them again, and now stopping unexpectedly so that all three of them rolled over together in a happy laughing heap of fur and arms and legs. It was such a romp as no one had ever had except in Narnia; and whether it was more like playing with a thunderstorm or playing with a kitten Lucy could never make up her mind. And the funny thing was that when all three finally lay together panting in the sun the girls no longer felt in the least tired or hungry or thirsty."

|

Unlike many who grew up in the church, I didn't discover The Chronicles of Narnia as a child. The first time I encountered this scene was when I read it aloud several years ago to my then seven-year-old daughter and four-year-old son. For days, my kids and I reveled in Lewis' magical, snow-covered world with its talking fauns and ethereal dryads, all the while absorbing key elements of the Christian story — God's care for his creation, the reality of evil, and the redemptive power of sacrificial love.

Then I read this scene, of the dignified Aslan leaping, laughing, chasing, tossing. A description of "such a romp as no one had ever seen."

I remember my breath caught in my throat. I remember my eyes filled. I remember I stopped reading for several seconds. My children had no idea what was going on, but I was stunned, discovering a possibility I'd never dreamed of before. God laughs? God romps? God… plays?

Those who know Lewis' novel will remember that this was hardly a moment for fun and games in Narnia. Though Aslan's resurrection had shifted the story towards a happy ending, though the evil White Witch's days were numbered, Aslan's kingdom was still in peril. War was ravaging the land and claiming innocent lives. Aslan's faithful were dejected and struggling, unaware that their Savior lived. Who would choose such a moment to play tag?

This is not a facetious question; I mean it in earnest. Growing up, I never heard a word about God (or Jesus) laughing, joking, or doing anything for fun. It would have been considered disrespectful — even heretical — to imagine the Son of God goofing around with his disciples, or playing hide-and-seek with the children who flocked to him. And yet, how many children do we know who flock to austere adults? Kids hate stodginess; they love adults who play.

Indeed, the very nature of play — its non-pragmatism, its spontaneity, its unapologetic rootedness in pleasure — would have struck my younger self as scandalous in relation to God. His holiness, I believed, required a certain solemnity and decorum. And anyway, he was in the serious business of saving a broken world. How could he have the time or inclination to play?

|

The ironic disconnect, though, is that play features everywhere in God's creation. It's a fundamental part of human childhood, and many, if not most wild animals play. According to some researchers, play burns up to 20% of the survival energy of young animals, despite the fact that play doesn't provide food, shelter, safety or any other outcome necessary for survival. Why would evolution favor such an apparently useless activity?

Inviting play into my life with God is not easy, as my religious vocabulary tends to lean in a different direction. Labor. Striving. Discipleship. Work. These words aren't wrong. But could it be that when we play — when we take ourselves less seriously, when we remember to laugh at our pious pretensions, when we invite creativity and spontaneity into our relationships with God, when we "waste" time that ought to be more "spiritually" spent — we who are created in God's image mirror the playfulness of our Maker?

In the spring of 2010, I made a silent retreat at the Abbey of Gethsemani, a Trappist monastery in central Kentucky. I had never spent five days in silent prayer before, but being both naive and Type A, I arrived at the Abbey armed and zealous. I had my Bible, I had my prayer books, and I had my lofty expectations. Most of all, I had an agenda — a lengthy laundry list I thought God and I would spend the week sorting out. Childhood hurts, family concerns, parenting issues… a whole slew of particulars needing urgent attention. In other words, I was ready to work.

About twelve hours later, after I'd prayed my laundry list a few zillion times and discovered nothing but exhaustion, I got a clue. I realized that I knew nothing about quieting my mind and heart before a God who wants me and not my pious to-do list. I realized that prayer involves a whole lot more than frenzied chatter. And I realized that if my retreat was going to benefit me in any way whatsoever, I would need first of all to calm the heck down.

These revelations made me miserable, and I spent the next couple of days walking the Abbey grounds, crying my eyes out. By day four, I was hollowed out, prayed out, cried out. I was wide, wide open.

It's difficult and even embarrassing to write about a vision; even the word feels grandiose. And yet a vision is what I saw. Not literally, not with my physical eyes. With my mind's eye, perhaps? My heart? My soul? A skeptic would say that four days of silence had messed with my imagination. Made me suggestible. Perhaps. All I know is that what I saw blessed me in a way I'll never forget. Even when my inner skeptic sneers, the blessing still resonates.

I was walking the Abbey grounds yet again, early in the morning. After a long stretch of shady woods, my path cleared, and I stood at the edge of a wide, sunny meadow, with golden-colored grass rippling in the breeze.

|

The image came out of nowhere — an image, incidentally, that my kids had long outgrown, and I hadn't thought about in years. I saw an enormous lion appear in the grass, too golden and gorgeous for language. A little girl with black curls like mine rode on his back, her hair streaming, her fingers clinging tight to his mane as he ran back and forth across the meadow, faster than wind. She tickled his neck. He leapt and frolicked. She screamed. He roared. Neither could stop laughing for joy.

The vision couldn't have lasted more than seconds. Micro-seconds. But it looked and felt like eternity. Maybe it was a picture of eternity. Timeless, heedless delight. Infinite love, infinite freedom. A God who plays.

A friend of mine, with whom I shared my Gethsemani story, sent me a small stuffed lion afterwards. My son keeps it on his bed now, but I cherish it, still. The note tied around the lion's neck reads, "May you always know a God who romps with you."

I hope I will. May you always know him, too.

Image credits: (1) Uncyclopedia.wikia.com; (2) Julia Hughes; and (3) In-Spirited Travel Log.