Michael Fitzpatrick is a parishioner at St. Mark's Episcopal Church in Palo Alto, CA. After growing up in the rural northwest, he served over five years in the U. S. Army as a Chaplain's Assistant, including two deployments to Iraq. After completing his military service, Michael has done graduate work in literature and philosophy. He is now finishing his PhD at Stanford University.

Last month on the 8th Day, we made a small recovery of Christian sexual ethics as a way to engage with contemporary attitudes towards the body and human sexuality. Too often the temptation of contemporary culture is to transform Christ into a sort of rubber stamp for prevailing mores. I hope we will bravely trust that our Creator calls us to something more, to live according to a pattern not of this world, but a pattern of the One who came to save this world. This month, let’s explore another part of what our Christian faith has to share with the human community: the sacrament of marriage.

Although marriage is bound up with various legal issues, in Christian practice marriage is imbued with a deep spiritual significance. As a sacrament, marriage is the act by which God’s grace transforms two people into one flesh (Gen. 2.24). This astonishing image captures not merely the physical act of sexual union, but the whole shape of a consummate life together, as emotions, goals, values, dreams, fears, and suffering are all felt in our body as much as their body (Eph. 5.28). Like all the sacraments, marital union declares that a permanent reality has come into being. To witness a wedding ceremony is to watch creation itself, to watch the One Who Creates All Things craft two separate lives into a single life. As the Book of Common Prayer instructs each person to say to the other, “Will you love, comfort, honor and keep them, in sickness and in health; and, forsaking all others, be faithful to them as long as you both shall live?”

|

|

Le Baiser by sculptor Auguste Rodin, bronze cast of the 1889 original.

|

At the heart of marriage understood as a sacrament is the vision of permanent faithfulness. Marriage is the union of two people faithful to each other, faithful without condition or expiration. Perhaps such an observation seems banal, but when we consider the fleeting nature of human relationships, it’s quite radical! To commit to a single person without a knowledge of the future contexts in which that faithfulness will be tested is an extraordinary leap of faith. As such, it can often seem as foolishness (1 Cor. 1) to the practical concerns of the non-Christian world. After all, why commit to just one person when you have no idea what you will want or care about 10, 20, 30 years from now?

These questions are hardly academic. In a rather fascinating discussion on Red Table Talk, the Smith ladies took up the question of polyamory—having open relationships with multiple partners. Red Table Talk is a discussion forum Jada Pinkett Smith hosts with her mom, Adrienne Banfield-Norris, and her daughter, Willow Smith, in which the ladies talk about, well, just about every subject under the sun.

This past May, Willow Smith shared with her mom and grandmother that she believes polyamory is the best way to have romantic relationships. It emphases individual freedom, allowing people to choose their relationship needs from moment to moment without burdensome expectations. Willow argues,

“Could you imagine being in a group and loving everyone equally, whether it be platonic or not? … With polyamory, I feel like the main foundation is the freedom to be able to create the relationship style that works for you and not just stepping into monogamy because everyone around says that is the right thing to do.”

With the emphasis on freedom, consent becomes the ultimate ethical standard, as her mom observed in response to her daughter’s comments, “Wanting to set up your life in a way that you can have what it is you want, I think anything goes as long as the intentions are clear.” What is important in life is having what we want, and as long as everyone consents to the relationship, “anything goes.”

|

|

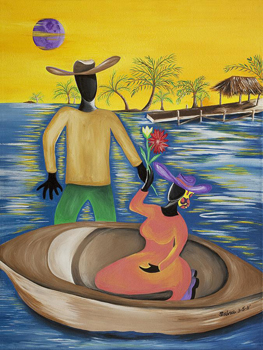

Why the Moon Smiles by Patricia Sabree (2011).

|

How should we as Christians think about this rejection of monogamy in favor of open relationships? How does Christ intersect with culture here? What I love about the Smith conversation is it highlights so many of the general values of our contemporary society: the freedom to do what you want, the rejection of what others say is the right thing, and the idea that anything goes so long as there is mutual consent.

These values feel fresh and modern, yet they were hardly unfamiliar to the biblical communities that followed Christ. St. Paul quotes as much in 1 Corinthians 6.12 when he acknowledges that we are all free to do what we want. “I have the right to do anything,” he says, “but not everything is beneficial.” Everything is permitted, we might paraphrase, but that doesn’t mean anything goes. Why not? Because freedom and the good are distinct values. Freedom and the good unite when opposing oppression, tyranny, and abuse. But when freedom becomes not being bound by any norms or responsibilities at all, not even by what is a good for human life, our freedom can become harmful. Sure, we are free to do whatever we want! But not everything we want is good.

In many ways, following Christ is an act of giving up our freedom to follow God’s will. To follow Christ is to choose the good, rather than anything goes. Willow Smith is quite free to reject monogamy as a norm of relationships, but is this a good choice? The Christian story grounds the picture of marriage as permanent faithfulness in the larger story of God’s faithfulness to creation. While Willow Smith may be getting what she wants in consensual polyamorous relationships, she is missing out on a deeper kind of love, a covenant love. As humans, among the many things we fear is that we will be rejected if another person comes to know us as we really are, or when we make mistakes, or (at the extreme) when we do evil acts. We experience faithfulness between each other as a fragile thing, easily lost and easily broken.

In response to this fragility, the Christian story tells us a narrative of God’s enduring faithfulness, where no matter how far the children of God wander from the good, God continues to love, discipline, instruct, and ultimately redeem the people. In the Exodus saga, the people are delivered from slavery in Egypt, but when their newfound freedom becomes difficult to bear, they pine for the slave whips of their former masters. Yet God endures, continually drawing them back to a promise of being a chosen people in a land to call their own. In later stories, the people commit infidelity by turning to idols, worshiping gods made by human hands rather than the true Creator. Yet God does not abandon them, but disciplines and restores, drawing them back to the Divine Embrace.

|

|

Couple Mourning Their Loss by Karl Hübner (1814-1879).

|

The stories culminate in Jesus, who as the very incarnation of God on earth is beaten, broken, and set upon a cross, where he forgives his abusers and gives up his life for the salvation of the world and the forgiveness of sins. No matter what we humans do to push away God’s love, that love saves the unworthy. “You see, at just the right time, when we were still powerless, Christ died for the ungodly” (Rom. 5.6) The Christian declaration of God’s covenant love for us culminates in St. Paul’s ecstatic declaration that “If God is for us, who can be against us? … Nothing in all creation will be able to separate us from the love of God that is in Christ Jesus our Lord!” (Rom. 8.31, 39).

This inseparable, covenant love is what permeates our universe, woven into the fabric of our lives. When we pursue the sacrament of marriage, we are choosing to incarnate this covenant love in response to God’s covenant love for us. We submit in trust to each other, as the church submits in trust to Christ (Eph. 5.24). We love our spouse, just as “Christ loved the church and gave himself up for her” (v. 25). Rather than aspiring to the freedom of our unrestricted desires, we have set our eyes on a greater hope, the covenant love of a savior who held nothing back for his beloved. The world’s pattern focuses on self-love and getting what we want; God’s pattern calls us to covenant love and faithful devotion to a single person no matter what in creation tries to separate us.

Our Christian witness in our contemporary culture should not be in a spirit of fear. We do not fear the culture that produces values different than ours. We need not take up arms or voting ballots to force our neighbors to live like we do. Such are the deeds of insecurity; whereas we who are wrapped in the everlasting embrace of covenant love act from the ultimate security. God will never let us go. But God also loves our neighbors, and wants this same ultimate security for them as much as for us. May we be neighbors who witness to the wider community just how much more blessing God has for all of us than the things we think we want for ourselves.

Michael Fitzpatrick welcomes comments and questions via m.c.fitzpatrick@outlook.com

Image credits: (1) Avant Garden & Home; (2) Fine Art America; and (3) Ayay.co.uk.