Michael Fitzpatrick is a parishioner at St. Mark's Episcopal Church in Palo Alto, CA. After growing up in the rural northwest, he served over five years in the U. S. Army as a Chaplain's Assistant, including two deployments to Iraq. After completing his military service, Michael has done graduate work in literature and philosophy. He is now finishing his PhD at Stanford University.

That we ought to work hard is taken for granted. That we ought to be at leisure is a much less common assumption. Consider this essay a defense of leisure. I write from the heart of Silicon Valley, surrounded by a startup culture that valorizes industrious entrepreneurship for the sake of large IPOs and the sirens’ lure of exorbitant wealth. Throughout my life it has been reinforced that the most important thing is to work hard, and anytime I’m not working or sleeping, I’m being lazy or wasting my time.

After all, “idle hands are the devil’s workshop.” That sounds like a Bible verse, even a proverb, and if you read Kenneth Taylor’s paraphrase of the Bible in English, the Living Bible, you’ll find it in Proverbs 16.27. The only problem is — that’s not what the original text actually says. The NIV translation merely reads, “A scoundrel plots evil.” Quite different! Scholars tend to think the famous idiom arises from an off-hand comment by St. Jerome that we should “engage in some occupation, so that the devil may always find us busy.”

|

|

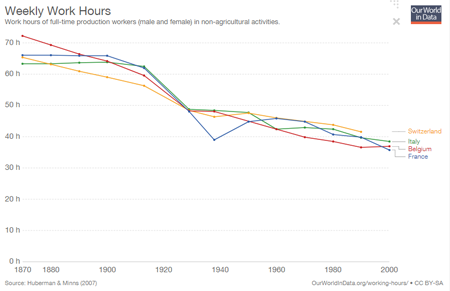

The change in work hours per week in some European countries since the 19th century.

|

This extra-biblical legacy set the table for our modern production-focused, high-stress culture. Max Weber famously suggested that “one does not only work in order to live, but one lives for the sake of one's work.” Prior to the introduction of labor laws, workers would often be forced by sheer need to work 60-70 hours a week in grueling factory conditions just to make enough to live on. The 40-hour work week, intended to be a constraint on this abuse (“work hard, just not too hard!”) has been easily circumvented by salaried positions, overtime, or retail-based dependency. Is our purpose in life really to work as hard as we can?

In a lovely little essay, “Life Without Principles,” Henry David Thoreau suggests that it is not. Like me, he experienced the unsettling social expectation that if he made lots of money, no matter the means, people assumed he was hard-working; but if he devoted himself to the betterment of his soul and education, then he was accused of being an idler.

If a man walk in the woods for love of them half of each day, he is in danger of being regarded as a loafer; but if he spends his whole day as a speculator, shearing off those woods and making earth bald before her time, he is esteemed an industrious and enterprising citizen. As if a town had no interest in its forests but to cut them down!

For Thoreau, there is work, and then there is work worth doing. Some work people get paid for is not worth doing, and by contrast work that is worth doing is often of no interest to a market economy. Walking in a forest, caring for an elderly person, helping a youth learn to drive, are all worthy labors, though unpaid. So is enjoying the fruits of those who create works of intrinsic value, such as reading a good book or listening to a folk singer share their music. Payment for the work is not the primary goal; if money is involved at all, it is purely a means to other ends.

In older times, these “other ends” were called leisure. Among the shames of our modernity is the equation of leisure with laziness or sloth. Because our market economies depend on production, and production depends on workers who produce, people have been kept desperate or greedy enough to perform menial labor so that production gets its workers. The blessed few who can get off work at a reasonable hour and get home to their families often find more work awaiting them—dishes to be washed, bathtubs to be cleaned, pipes to be repaired. And all for what? Just to collapse into bed exhausted only to repeat the same on the morrow? We can feel we have no choice because if we do not fill every waking moment with obligations, we will not be hard-working people.

|

|

Walden Pond by Frederick Childe Hassam.

|

Nor should the word ‘hard’ in the phrase “hard-working” be taken as an indicator of work worth doing. Thomas Aquinas famously wrote in the Summa Theologia that “virtue essentially regards the good rather the difficult. Hence the greatness of a virtue is measured according to its goodness rather than its difficulty” (ST II-II.123.12). Our cultural emphasis on long hours, back-breaking activities, dangerous working conditions, and other forms of intensive labor has replaced the good with the difficult. Most people regard my military deployment into combat in Iraq as justified because I received combat and hazard pay. Since I received my due wages, I can be expected to perform any duties whatsoever, no matter how difficult! But what about whether the work I was doing was good?

The goal of work is not wages but leisure. Leisure never originally meant doing nothing, being lazy, some kind of bored existence flipping through new movies on one’s streaming service. Aristotle suggested that we rest in order to be prepared to work, and we work in order to have subsistence so that we can be at leisure. Rest leads to work which leads to leisure. Leisure was the goal of work, not an excuse to get out of work. And what is this goal? To be at leisure, Aristotle thought, is to be free to practice the “liberal arts,” that is, the activities only a free person has the time to engage in. In other words, we labor to create a subsistence for each other so as to become free to do the activities that are the reason for living.

The cultivation of a garden, for example, is to be at leisure. Gardening takes an enormous amount of diligence and attention to successfully care for plants, from trimming stems to water to caring for the soil to warding off pests. To garden requires harmonizing our desires with the needs of other living creatures, because we want to, not because we have to. Gardening cultivates our soul at the same time as we cultivate our plants. When labor is an expression of what we love, we have ceased to work, and instead are at leisure.

Some are fortunate that their leisure is also the source of their subsistence. They have a rare and joyous existence. For the rest of us, the real danger is that we become so consumed by the demands of our work that we never find ourselves at leisure. Yet even those who enjoy their work endanger our concept of leisure because their lives nonetheless imply that to be a good human is to spend the majority of one’s time supporting the production of wealth, as if someone who devoted their life to leisure without being paid for it has somehow lived a worthless life.

|

|

Painting of Caribbean school girls having a moment of leisure.

|

Josef Pieper, in his marvelous little book Leisure, suggests that a foundational practice of leisure is learning how to really see the world. In the hurried pace of our Google calendar appointments, we often flit from one task to the next, trying to keep abreast with the ever-quickening pace of our profession so that we can justify our wages (in the world of academia wherein I reside, this pace has reached an obscene velocity). In such a sphere, Pieper contends that the most subversive thing we can do is slow down, choose to be with the world, and actually see the person or the craft in front of us. A person who truly sees those around them for their own sake might have a more worthwhile life than the successful entrepreneur with an impressive stock portfolio who has never seen a world outside of their own ambition.

Pieper translates Psalm 46.10 as, “Be at leisure, and know that I am God.” As we move through the Advent season towards Christmastide, can we use these contemplative seasons to shift the aim of our life from “getting the work done” to “creating space for leisure”? The first step is to let go of the association of leisure with laziness, and give ourselves permission to orient our days and weeks around work worth doing (which is often not what market economies pay for). Serving at our parishes in the children’s pageant, volunteering at a prison ministry, taking the time to laugh once more at that dad-joke you’ve heard a dozen times, or even simply hugging a beloved with an embrace that has no definite expiration; these are the deeds of leisure, of people fortunate and free enough to do work worth doing. Work that is so valuable Wall Street cannot put a price on it: the work of leisure.

Michael Fitzpatrick welcomes comments and questions via m.c.fitzpatrick@outlook.com

Image credits: (1) World Economic Forum; (2) Painting Mania; and (3) Bored Art.