Michael Fitzpatrick is a parishioner at St. Mark's Episcopal Church in Palo Alto, CA. After growing up in the rural northwest, he served over five years in the U. S. Army as a Chaplain's Assistant, including two deployments to Iraq. After completing his military service, Michael has done graduate work in literature and philosophy. He is now finishing his PhD at Stanford University.

I’ve been reflecting recently on the ways Christians have used the authority of God and the Church to justify existing political institutions, forms of government, and even particular policies.

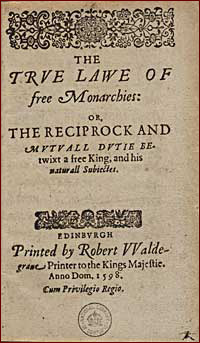

To start with a familiar example, the divine right of rule alleged by English and European monarchs in the 16th and 17th centuries. Kings such as James the 1st of England declared against Enlightenment proposals of social contracts and consent that the authority of a monarch is established directly by the Most High God, and that divinely-appointed rulers hold the throne by right, answerable to their Creator alone. Thus, there can be no accountability of a king to the people governed by them. Nor can a king be bound by any rights of the people, since the king is subject to no external constraints apart from God. As the centuries following the enactment of the Magna Carta led to more and more calls to restrict the powers of monarchs, monarchs sought to solidify their power by appeal to divine right.

A more recent instance of this phenomena occurred in apartheid South Africa. In an incisive article by Kevin Giles for CBE International, he relays the astonishing story of how the Reformed Church of South Africa, South Africa’s largest denomination and primarily made up of white Dutch Afrikaners, supported the forced segregation and subjugation of South Africa’s black population during the 20th century. For Afrikaner theologians, it was God’s will that the races should be kept separate, with those appointed as superior races to determine the rights and needs of inferior races. Apartheid was justified on the basis of biblical stories like the Tower of Babel, where, Afrikaner theologians insisted, God had divided the people into distinct ethnic and linguistic communities as a permanent separation.

|

|

Tract secretly written by James the 1st of England to justify his claim to the throne.

|

Appeals to divine sanction continue to this day. Three years ago, U. S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions defended the White House’s “zero-tolerance” policy for illegal immigration on the grounds that the Bible commands people to obey the government, so long as its policies are consistent (a remark that would have come as quite a surprise to theologians like Karl Barth and Dietrich Bonhoeffer!).

Sessions said during a 2018 press conference, “Persons who violate the law of our nation are subject to prosecution. If you violate the law, you subject yourself to prosecution. I would cite you to the Apostle Paul and his clear and wise command in Romans 13, to obey the laws of the government because God has ordained the government for his purposes. Orderly and lawful processes are good in themselves. Consistent and fair application of the law is in itself a good and moral thing, and that protects the weak and protects the lawful.”

I offer up these examples with the hope that as Christians we share a common revulsion to the Holy God being used in such a sacrilegious manner to prop up earthly human powers. There are at least two ways these invocations of divine endorsement should offend honest faith. The first of course is their use to justify unjust governments and acts of subjugation. Such things must be repugnant for us who believe that “those who oppress the poor [and blacks, and immigrants, etc.] insult their Maker” (Prov. 14.31).

The second offense is that these appeals assume that God has a preference amongst fallible, human forms of government. Don’t we as Christ followers believe God has made the risen Jesus Lord over the coming Kingdom to which all human governments will be answerable? Because we are citizens of the Kingdom of God, we resist all attempts to reduce God’s Kingdom to human forms of power. As Episcopal priest Winnie Varghese writes in her book Church Meets World, “Our church does not teach that the way of the world is God’s way. We, as followers of Jesus, teach the opposite. We teach that the ways of the world are the ways of the powers and principalities. The ways of God are to be found . . . in the places where it is not safe to go because you might see something that causes you to question the way things are.”

|

|

Untitled apartheid protest drawing by Keith Haring ca.1984, curated at the De Young Museum.

|

When monarchies or apartheid parliaments or departments of justice appeal to God for sanction, they are saying that the way of the world is God’s way. When the Church endorses these forms of governments and policies, we do the same, using the authority of the Church to deem as timeless a transitory form of politics. The Church has survived empires, feudalism, monarchies, colonialism, communism, and republicanism, all seeking her authorization and support, yet all proving to be fleeting forms of political organization in the sweep of history. The Church has been at our best when we remain at a critical distance from earthly powers and principalities, so that we can criticize those powers and their abuses in the name of the Kingdom, the only perfect standard of justice.

I expect few would demur from these examples and conclusions, yet we may miss the most important lesson they contain. In all these cases, Christians who sought to justify their existing political patterns as God’s will would have made similar contrasts with respect to other nations and time periods. There is a basic human temptation to regard our forms of politics as the forms God enjoins. Never was this more apparent than in the United States during the beginnings of the Cold War, when “under God” was added to the American pledge of allegiance to sharpen the contrast between Western democratic republics and “godless” communism in Europe and Asia. Since democracy and liberalism are our forms of government, of course God supports them!

But… does God? Are we not making the same mistake as the supporters of monarchies or apartheid republics when we presume that God supports our electoral systems, our voting, our representative government, and even our constitutional rights? Even if we contend that, in contrast to monarchies or apartheid, our forms of government are just (a tenuous claim, especially when viewed through non-Western eyes), isn’t it a confusion to assume that because God commands our acts of justice, therefore God endorses our earthly forms of government by which we achieve that justice?

These questions have been on my mind as I’ve observed Western churches over the past few years pass resolutions and issue official statements endorsing highly-specific policies when it comes to elections, voting, representation, and democracy. My own Presiding Bishop, the Most Rev. Michael Curry, has repeatedly advocated for a Christian duty to vote during U. S. elections. Yet Anglican political commentator Peter Hitchens has suggested that the cause of justice may require us not to vote, to no longer uphold a system of sham elections or arbitrary political candidates or that disenfranchises citizens. What if by upholding the electoral system and the right to vote, the Church inadvertently opposes the justice the Kingdom calls for?

| |

|

Russian icon depicting Shadrach, Meshach and Abednego refusing to bow to the king of Babylon's image.

|

The possibility is less implausible than it may seem. Political philosopher Alex Guerrero has pointed out that when ancient Greeks first formulated the concept of democracy, elections were seen as opposed to democracy, serving as instruments of oligarchs to foment partisan factions and shore up popular support. True democracy according to the Greeks meant forming governmental bodies by lottery, a random selection from the citizenry, a practice we still use when composing juries in our judiciary. Hitchens and Guerrero contend that it is the system of elections itself that is causing the severe partisan divide today, and Guerrero advocates for a return to citizen-commissions constituted by lottery.

Whatever we make of these proposals, as Christians we are foremost citizens of the Kingdom, which is never allied with the pattern of this world. By resisting an alliance of the Church with the forms of this world, we remain ever free to criticize them in the name of God’s justice. The Church should be as free to criticize democracy and elections as it should be to criticize monarchies and apartheid and immigration policies. There can be no Christian duty to vote or not vote, only a duty to advocate God’s justice, whether by using the instruments of human politics, or opposing them.

We can see the error of aligning God’s will with the ways we humans organize ourselves when we look at forms of government and forms of injustice other than our own. With the grace of humility we can avoid the same temptation when it comes to our liberal democracies and political parties. Which is not to say the Church should be silent about politics, but only to say that when the Church speaks, it should always be as a word of judgment on the existing political order, not for the sake of the Church’s power (God forbid!), but in the name of the One “with angels, authorities, and powers in submission to him” (1 Peter 3.22).

Michael Fitzpatrick welcomes comments and questions via m.c.fitzpatrick@outlook.com

Image credits: (1) Wikipedia.org; (2) de Young Museum, San Francisco.; and (3) www.myartprints.co.uk.