This month Christians around the world will begin our season of Lent. By a crazy quirk of the calendar, in 2018 Ash Wednesday is also Valentine's Day, February 14. And Easter falls on April Fools' Day.

In Flannery O'Connor's short story Revelation, the character Mrs. Turpin is a good and decent woman who did everything right — except that she was a racist. She was blinded to this ugly reality by her self-righteousness. She was a person, writes O'Connor, who when she entered heaven needed "even her virtues burned away."

Mrs. Turpin has provoked me to try a different Lenten discipline, one with the help of a Jewish ritual. I'd like not only to repent of my unrighteous acts and attitudes. I'd also like to repudiate my efforts at righteousness.

There's a thin line between true righteousness and self-righteousness, between sanctification that beautifies me and sanctimony that blinds me. The losing battle of self-justification is hard to quit.

|

|

Receiving ashes in Papua New Guinea.

|

Our Jewish forbears have an ancient ritual to address this problem. It's called Kol Nidre — in Aramaic, "all vows." The Kol Nidre is a declaration that is recited at the beginning of the service on the eve of Yom Kippur (Day of Atonement).

The service begins with a prayer: "In the tribunal of heaven and the tribunal of earth, by the permission of God — blessed be He — and by the permission of this holy congregation, we hold it lawful to pray with the transgressors." That is, we gladly take our place among the sinners rather than the saintly.

The cantor then chants the prayer that begins with the first two words "Kol Nidre."

"All vows, obligations, oaths, and anathemas, whether called 'ḳonam,' 'ḳonas,' or by any other name, which we may vow, or swear, or pledge, or whereby we may be bound, from this Day of Atonement until the next (whose happy coming we await), we do repent. May they be deemed absolved, forgiven, annulled, and void, and made of no effect; they shall not bind us nor have power over us. The vows shall not be reckoned vows; the obligations shall not be obligatory; nor the oaths be oaths."

The leader and the congregation respond by quoting Numbers 15:26: "And it shall be forgiven all the congregation of the children of Israel, and the stranger that sojourns among them, seeing all the people were in ignorance."

The idea behind Kol Nidre is that however well-intended, I break my promises to God. And all my broken promises can become a horrible burden. That shouldn't surprise me. And so I need forgiveness for "all vows" of righteousness, for all my efforts to earn the love of God. I thus repent of all my vows, pledges and promises of righteousness. I'm forgiven for all my misplaced zeal, however earnest I thought I was.

|

|

Ash Wednesday in Australia.

|

In his book In God's Shadow (2012), Michael Walzer of Princeton observes that Israel began with two different but related covenants — one with Abraham based upon kinship, family, and birthright as a chosen people, and another with Moses based upon a legal covenant, a nation, and law. In Romans 4, Paul repudiates both of these foundational appeals for divine favor.

Paul once boasted on both accounts. He bragged that he was a "Hebrew of Hebrews" who could trace his ancestry to the tribe of Benjamin. As for the Mosaic law, he boasted that he was "zealous" and "faultless." But Paul later repudiated his vows of righteousness: "whatever was to my profit I now consider loss."

Counting how many times a word occurs in the Bible can lead to dubious interpretations. But Romans 4 is a glaring exception. At least 10 times Paul uses the word "credit" to describe our relationship with God. A credit is a free gift; it's the opposite of a wage that is paid for work or an obligation that is earned.

No one can curry God's favor by keeping the Mosaic law, by claiming kinship with Abraham, or by any other well-intentioned vow — like those we make for Lent.

But everyone can receive a free gift — even Gentiles, says Paul, who are not of Abrahamic ancestry and who are ignorant of the Mosaic law.

All the promises of God's free love come to us "by faith," says Paul. Faith, said Luther, is the beggar's empty hand that can do nothing except receive a gift with gratitude.

So, thank God for this liturgical repudiation of my chronic self-righteousness. In his book of poetry called Idiot Psalms (2014), Scott Cairns ponders the implications of this ancient Jewish ritual. The poem is called Kol Nidre.

"Good to reconsider, and then to disavow

whatever mitigations one has let usurp,

eclipse, or glibly water down whatever good

he may have thought to offer. Some untoward something

will often sprout from any swollen hull thus sown.

The unforeseen is guaranteed to flourish well

beyond the harried terms of any vow expressed

from one's more narrow sense or solitary will.Good therefore to have another go at what

might prove of use beyond one's dim intention, no?

Good thereafter to unsay, recant what harm

has billowed, subsequent, from ill-considered

promise. Good that one prepare ever to repent."

|

|

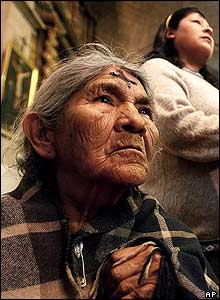

Receiving ashes in the United States.

|

Lenten disciplines can serve a positive purpose, especially in our culture of indulgence and entitlement. In past years I've abstained from meat and alcohol. One Lent I ate only one meal a day. That was hard. All things considered, I think I was better off for those disciplines.

I find it a lot harder, though, in our culture of merit, to repudiate my "vows" of righteousness and my many self-justifications, my chronic efforts to curry God's favor. So, in the spirit of Kol Nidre, this Lent I'll turn away from my vows of righteousness. And I'll turn to God, who promises to "credit" me with his free gift of love.

For further reflection

Edwina Gateley

Let Your God Love You

Be silent.

Be still.

Alone.

Empty

Before your God.

Say nothing.

Ask nothing.

Be silent.

Be still.

Let your God look upon you.

That is all.

God knows.

God understands.

God loves you

With an enormous love,

And only wants

To look upon you

With that love.

Quiet.

Still.

Be.Let your God—

Love you.

Image credits: (1) SocietyofOurLady.net; (2) Life's Rich Pageant blog; and (3) Traditio; the Traditional Roman Catholic Network.