I had an "NPR moment" a few days ago. I was driving home, listening to NewYork Times columnist David Brooks give an interview on his new book, The Road to Character, when he said something that made me turn my car around. "I like the word 'sin,'" he said, "and I think it's necessary to bring it back. It reminds us that life is a moral occasion."

As Brooks went on to talk about how religion gives us essential words (words like sin, grace, and holiness) to help us think about the inner life, I turned my car around, drove to the nearest bookstore, and grabbed a copy of his book from the New Nonfiction Hardcovers table. Here are a couple of excerpts:

"Today the word sin has lost its power and awesome intensity. It’s used most frequently in the context of fattening desserts. Most people in mainstream conversation don’t talk much about individual sin. If they talk about human evil at all, then that evil is most often located in the structures of society — in inequality, oppression, racism, and so on — not in the human breast."

"When modern culture tries to replace sin with ideas like error or insensitivity, or tries to banish words like virtue, character, evil, or vice altogether, that doesn’t make life any less moral. It just means we think and talk about these choices less clearly, and become increasingly blind to the moral stakes of everyday life."

I'm not friends with many people — religious or secular — who like the word sin. Many Christians, particularly those of us who have moved away from fundamentalism, actively dislike the word. We associate it with paralyzing guilt and eternal hellfire. Too often, sin is a word that has frightened us away from God rather than drawn us closer to him.

We also distrust the word because we've seen how easily it can be manipulated to justify one moral agenda over another. In some churches, abortion and homosexuality are the big, bad sins, while our rape of this planet and our systemic disregard for the poor are not. In others, the capital "S" sins include hawkish foreign policy, capital punishment, and corporate greed. Not unloving sex, mind-numbing busyness, and intellectual snobbery.

In short, the word carries serious baggage. So why, I'm wondering, did I feel relief when Brooks said he likes it? Why did I nod as if to say, "Yes, I like it, too! And I need it. Differently than I needed it before, but still. I need it."

I read a news article about Silicon Valley recently, in which a high school student compared northern Californians to ducks swimming in a pond. Our movements appear smooth and easy at all times. We glide, we part the water, we splash and play. No one (we make sure) peeks beneath the surface. No one sees the truth. The constant, furious paddling.

Maybe I'm drawn to the word "sin" because it exposes my burdensome secret. It tells the truth, which is that I am a beautiful mess — made in God's divine image, but mired in a human brokenness that wars against its own salvation. To use the word "sin" is to insist on something more profound and more clarifying than, "I make mistakes," or "I have issues." To use the word sin is to stop the desperate paddling, and admit at last that I cannot cross the vast water alone.

Maybe I'm drawn to the word "sin" because it exposes my burdensome secret. It tells the truth, which is that I am a beautiful mess — made in God's divine image, but mired in a human brokenness that wars against its own salvation. To use the word "sin" is to insist on something more profound and more clarifying than, "I make mistakes," or "I have issues." To use the word sin is to stop the desperate paddling, and admit at last that I cannot cross the vast water alone.

What is sin? Growing up, I was taught that sin is "breaking God's laws." Or "missing the mark," as an archer misses his target. Or "committing immoral acts." These definitions aren't wrong, but I no longer find them big enough. They assume that sin is a problem primarily because it angers God. But God's temper is not what's at stake; he's more than capable of managing his own emotions. Sin is a problem because it kills. It kills me.

I think sin is a refusal to become fully human. It's anything that interferes with the opening up of my whole heart to God, to others, to creation, to myself. Sin is estrangement, disconnection, sterility, disharmony. It's the slow accumulation of dust, choking the heart. It's the sludge that slows me down, that says, "Quit. Stop walking. Lie down. Change is impossible."

Sin is apathy. Care-less-ness. A frightened resistance to an engaged life. Sin is the opposite of creativity, the opposite of abundance, the opposite of flourishing. It is a walking death. My life, precious to God, dying.

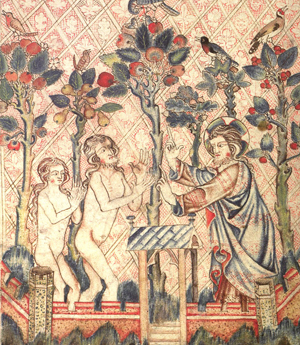

A good friend told me this week about a sermon she heard recently on the "forbidden tree" of Genesis 2. Why on earth, the preacher asked, would a loving God plant a forbidden tree right smack in the middle of Eden? Basically ensuring that Adam and Eve would walk past it every single day, gazing, circling, wondering? Was God being cruel? To what end would he tempt his children in this daily way?

"Life is a moral occasion," Brooks said in his interview, and sin is what reminds us that this is true. My forbidden tree doesn't look like yours, and it takes on different forms as circumstances dictate. But it's planted in the center of my life for a reason. It's the thing that draws my gaze. The thing that keeps me hungry. The thing I circle around and around, trying to crack, trying to conquer. It attracts and repels me by turn. But I am not meant to cut it down. I'm meant to live in humble awareness of its place in the garden. I'm meant to orient my life around the gardener instead — the gardener who planted the tree for my salvation. Not my undoing.

Life is a moral occasion precisely because God designed it to be. Somehow, this drama, this circling, this embattled movement towards the tree and back — it grows something in me worth growing. Every time I take sin seriously, every time I wrestle my gaze back towards my Creator, my inner life deepens. I become more fully human. More fully God's.

I like the "s" word. I like high stakes. I like believing that our souls are worth fighting for.

Image credits: St. Louis University Libraries.