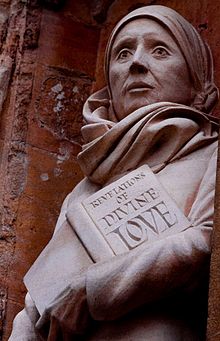

On May 8 the Episcopal and Lutheran churches will celebrate the feast day of one of the most famous non-saints in church history, Julian of Norwich (1342–1416). Catholics will do the same on May 13. During Holy Week not long ago, I read Julian's Revelations of Divine Love. And believe me, that was a good decision.

In the first few days of May of 1373, an obscure woman who called herself "a simple, uneducated creature" lay on her death bed for "three days and three nights." She said she was "thirty and a half years old." On the fourth night she received the last rites of the Catholic Church "and did not expect to live until morning."

On the night of May 8, she asked to be propped up in her bed. By this time her eyes were fixed, her lower body was numb, she could not speak, and a priest had come to preside over her death. He set a crucifix before the woman at the foot of her bed. What happened next, as they say, is history.

Beginning at four in the morning, and lasting well past the middle of the day, Julian of Norwich had a series of fifteen visions, showings, or revelations as she gazed at the crucifix. She then had a sixteenth revelation on the following night that confirmed to her the authenticity of her experiences, which visions she was otherwise tempted to attribute to delirium.

|

"I never asked for any bodily vision," writes Julian, "or any kind of revelation from God." And yet she had the audacity to believe that God had in fact spoken to her in order to benefit all humanity: "I had a true and powerful perception that it was he himself who showed this to me without any intermediary."

Soon after she recovered, Julian wrote a summary of her revelations, which we now know as her Short Text (35 pages). Twenty years later, as she continued to reflect on her visions, she wrote a fuller description called the Long Text (125 pages). Remarkably, this obscure text by an unknown woman received little attention for 300 years, until it was first published in 1670. Today we remember Julian for having written the first surviving book composed by a woman in English, Revelations of Divine Love. How she and her manuscript ever survived is both mystery and miracle.

There have now been many editions of Revelations of Divine Love, but I read the one by Barry Windeatt (below), which is likely the best one in English. His translations of both the long and short texts are preceded by an excellent forty-page introduction. Julian, he says, was a profoundly original and radical thinker who wrote at length about the motherhood of God. For her sin was "nothing." Indeed, "God also revealed that sin shall be no shame to man, but his glory," because the love of God is infinitely greater. And however extreme our sin and suffering, nothing can separate us from the motherly love of God. Julian also insisted that it was "the greatest impossibility" for there to be any anger of any kind in God, for "he is nothing but goodness." Her book, says Windeatt, is "a marvel of stylistic subtlety and grace" that "combines an unmannered rhetorical sophistication with some of the energy and fluidity of a more oral style."

Writing in vernacular English rather than in the Latin of the Oxford and Cambridge intellectuals or the French of the royal court, Julian's message was simple but radical: "I was taught that love was our Lord's meaning."

Endless love, blessed love, unutterable love, and tender love, which love has no beginning or end.

"How intimately he loves us," she writes. We are "known and loved from without beginning." Whether falling into despair or rising in joy, we are "always inestimably protected in one love."

"He has made everything that is made for love — and by the same love everything is sustained and will be without end."

"Though the three persons of the Trinity are all equal in themselves, my soul understood love most clearly, yes, and God wants us to consider and enjoy love in everything. And this is the knowledge of which we are most ignorant; for some of us believe that God is almighty and has power to do everything, and that he has wisdom and knows how to do everything, but that he is all love and is willing to do everything — there we stop."

"All shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner of things shall be well."

_f._97_smr.png) |

On the last page of her long text in chapter 86 she concludes: "From the time these things were first revealed I had often wanted to know what was our Lord's meaning. It was more than fifteen years after that I was answered in my spirit's understanding. 'You would know our Lord's meaning in this thing? Know it well. Love was his meaning. Who showed it to you? Love. What did he show you? Love. Why did he show it? For love. Hold on to this and you will know and understand love more and more. But you will not know or learn anything else — ever."

And so, says Julian, "the greatest honor we can give almighty God is to live gladly because of the knowledge of his love."

For more on this beloved saint see the books by Amy Frykholm, Julian of Norwich, A Contemplative Biography (Brewster, MA: Paraclete Press, 2010), 147pp; Amy Laura Hall, Laughing at the Devil: Seeing the World with Julian of Norwich (Durham: Duke University Press, 2018), 124pp; and Julian of Norwich, Revelations of Divine Love, translated with an Introduction and Notes by Barry Windeatt (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015), 214pp.

Dan Clendenin: dan@journeywithjesus.net