In my Eighth Day essay last month, I described the person and work of the French sociologist Jacques Ellul (1912–1994) as an inspirational example of a critique of our technological society. There are many ways such a critique might proceed, but this month I want to highlight three of our biggest challenges.

Big Data is now the new oil, which is why some people call it an "extraction" industry. Big Data is so big that it's hard to comprehend. Facebook has upwards of 3 billion monthly users on its platforms — nearly 40% of the world population, from whom it collects and correlates data. It purchases even more data from outside sources.

Back in 2016 — over four years ago, which is an eternity in the tech world, Propublica collected more than 52,000 unique attributes that Facebook has used to classify users. Google gathers even more data. And with three times the population of the United States, and an authoritarian government, China collects more than both of them. With this Big Data, tech companies compile extremely detailed profiles of every single one of us.

But the real force multiplier is metadata, or the "data about the data," like where you were when you bought ice cream on Tuesday, what flavor you bought, how many times you have been to that store, what model of car you were driving, who was in the car with you, the precise time of day, every single post you've made on Facebook, what time you go to bed and wake up, etc. Metadata has unimaginable value because of its nearly incomprehensible scale, and its ability to create powerful algorithms to manipulate our behavior.

|

|

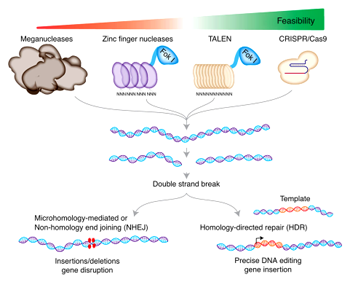

The different generations of nucleases used for genome editing and the DNA repair pathways used to modify target DNA.

|

So, if a white skinhead or an enemy government is willing to pay Google or Facebook, they will target a sophisticated advertisement at all the people in the world who share an identical profile in common — like every single person who voted a certain way, reads Tolstoy, likes licorice, drives a blue Prius, types poorly on their mobile phone, and who wants to buy a hammer for Christmas. This sounds crazy and farfetched, but it's not. It's terrifying and creepy.

Metadata gave rise to the aphorism that "users are not the customer, they are the product." Thanks to the algorithms that are based upon metadata, it is a tool of incredible behavioral prediction and manipulation. Artificial intelligence that uses such metadata has what Roger McNamee calls "nearly perfect information about us."

Second, critics are also warning us of mass behavioral addiction. The average user spends about three hours a day looking at their smart phone screen. Only 12% spend less than an hour. In one study by the research firm Dscout, the average number of touches, taps, swipes, and clicks was 2,617 per person per day. A 2015 study by Common Sense Media found that teenagers consume nine hours of media a day. A British study documented that children spend more time indoors than prisoners.

This mass behavioral addiction is not an accident. Nor is it a character flaw in the user. Rather, it is the result of carefully engineered designs by the technology companies. Indeed, it is their very business model.

The science of engineering compulsion is called "persuasive technology," which is the title of the gold standard book on this subject by the Stanford professor B.J. Fogg. You can take a course on it at many universities. Persuasive technology is a complex combination of software architecture, applied psychology, behavioral economics, propaganda, variable reward, and techniques that are used to program slot machines. The goal is not mere "engagement" with an app or a site, it is addiction.

Tristan Harris, a former Google design ethicist who took Fogg's course at Stanford, calls it "brain hacking." Similarly, says McNamee, with persuasive technologies, "Artificial Intelligence has a high bandwidth connection directly into the cerebral cortex of more than two billion humans who have no idea what they are up against."

The real business of Silicon Valley is not programming apps but programming us. Forget about the naive mantra that "technology is neutral." Any number of high placed tech insiders like Sean Parker, the founding president of Facebook, have admitted this in public. The algorithms that are based upon metadata have as their goal behavior modification, of turning habits into addictions as the proven recipe for corporate profits.

Third, there is the phenomenon of comprehensive global surveillance. I recently read Edward Snowden's memoir Permanent Record (2019). It details how in May of 2013 he flew to Hong Kong, where he documented to the journalists Laura Poitras and Glenn Greenwald how the United States' NSA (and partner countries) operated a vast, secretive, and unimaginably powerful system of mass surveillance that was unaccountable to any judicial warrants, public or congressional oversight, and that flagrantly violated the Constitution (cf. the Fourth Amendment). In effect, the American government was digitally spying on anyone it wanted, through its "bulk collection" of data and metadata, including spying on at least 35 world leaders like Angela Merkel's cell phone.

"Deep in a tunnel under a pineapple field," Snowden writes, "I sat at a terminal from which I had practically unlimited access to the communications of nearly every man, woman, and child on earth who'd ever dialed a phone or touched a computer." And again: "It was, simply put, the closest thing to science fiction I've ever seen in science fact: an interface that allows you to type in pretty much anyone's address, telephone number, or IP address, and then basically go through the recent history of their online activity. In some cases you could even play back recordings of their online sessions, so that the screen you'd be looking at was their screen, whatever was on their desktop."

|

|

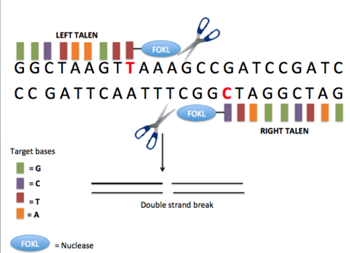

General overview of the TALEN process.

|

Apart from the legal, political, and ethical ramifications of mass surveillance, for Snowden this was first and foremost a radical subversion of the norms of a liberal, democratic society. And so whereas he has been called many things — a traitor, leaker, dissident, spy, and scapegoat, he considers himself a patriotic whistle blower. That's why he released his book on September 17, 2019, which happens to be Constitution Day.

Snowden's story is more than seven years old, once again an eternity in the tech world, and its focus is on government surveillance. It doesn't consider corporate surveillance by companies like Facebook, Google, Amazon, and Apple. That's the subject of the mind-blowing book by Shoshana Zuboff of Harvard Business School, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism (2019). She explores the ominous world of "behavioral futures markets," where "predictions about our behavior are bought and sold," and "the production of goods and services is subordinated to new means of behavioral modification."

The week that I read Snowden's memoir, Google made two public announcements. First, device chief Rick Osterloh said that anyone with a smart device in their home like Nest or Amazon Echo should advise their house guests that their conversations were being recorded (and that he so warns his own guests).

Second, in the October 23, 2019 edition of Nature, Google announced that their quantum computer called Sycamore solved a particularly difficult problem in 200 seconds. It also claimed that the world’s current fastest classical computer, IBM's Summit, would take 10,000 years to solve that same problem. The experts debate these claims pro and con, but this gives us an idea of the immense power of computing today, and how that is being used for big data collection, mass behavioral addiction, and comprehensive global surveillance.

What can we do in response to these powerful forces? Being aware and informed is a beginning. Jacques Ellul challenged us to have a "radical discussion" about our technological society: "The question now is whether people are prepared or not to realize that they are dominated by technology. And to realize that technology oppresses them, forces them to undertake certain obligations and conditions them. Their freedom begins when they become conscious of these things."

There are also small and symbolic acts that we can all take that are nonetheless important, like digital-free dinners. I turn my cell phone off at night. Several years ago I quit Facebook and Twitter. There are excellent resources, too, like Common Sense Media and the Center for Humane Technology. Finally, we can read some of the many good books that are out there (below).

I especially commend the book Digital Minimalism by the computer scientist Cal Newport. He offers a thirty-day plan to "digitally declutter" your life that thousands of people have found helpful. This won't be easy, he admits, but many people, each in their own way as their personal circumstances permit, are starting to relate to these technologies in much healthier ways. So, if you dare, join this "bold act of resistance" and reclaim your life.

FOOTNOTE: On Propublica, see https://www.propublica.org/article/facebook-doesnt-tell-users-everything-it-really-knows-about-them

For Further Reading

Dave Eggers, The Circle: A Novel (New York: Knopf, 2013), 491pp.

Franklin Foer, World without Mind: The Existential Threat of Big Tech (New York: Penguin Press, 2017), 257pp.

Jaron Lanier, Ten Arguments for Deleting Your Social Media Accounts Right Now (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2018), 146pp.

Roger McNamee, Zucked: Waking Up to the Facebook Catastrophe (New York: Penguin Press, 2019), 336pp.

Evgeny Morozov, To Save Everything, Click Here; The Folly of Technological Solutionism (New York: PublicAffairs, 2013), 432pp.

Cal Newport, Digital Minimalism: Choosing a Focused Life in a Noisy World (New York: Portfolio Penguin, 2019), 284pp.

Robert Scheer, with Sara Beladi, They Know Everything About You; How Data-Collecting Corporations and Snooping Government Agencies Are Destroying Democracy (New York: Nation Books, 2015), 256pp.

Edward Snowden, Permanent Record (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2019), 339pp.

Sherry Turkle, Reclaiming Conversation; The Power of Talk in a Digital Age (New York: Penguin Press, 2015), 436pp.

Ellen Ullman, Life in Code: A Personal History of Technology (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2017), 306pp.

Curtis White, We, Robots: Staying Human in the Age of Big Data (Brooklyn: Melville House, 2015), 284pp.

Shoshana Zuboff, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism (New York: Public Affairs, 2019), 691pp.

Dan Clendenin: dan@journeywithjesus.net

Image credits: (1, 2) Wikipedia.org.