For What I Have Received…

By Debie Thomas

I spent a few hours at my church this week, preparing Lenten resources for parishioners. Aside from devotionals, activity sheets, and coloring books, I assembled little takeout boxes of "graces" — prayers of thanksgiving, typed out on strips of paper — for families to use at home between now and Easter. In the process, I thought a great deal about what I'm thankful for. One can't read the words, "We give you thanks, oh blessed Lord," and "We praise your name for these your many blessings," a few gazillion times without giving some thought to gratitude.

In last week's column, I wrote that I'm very thankful for my conservative evangelical upbringing. Though my faith is moving in a different direction these days, I would no more sever my evangelical roots than I would sever a limb. My early formation grounded me, nourished me, and shaped me. Here, for starters, is some of what I'm grateful for as I look back on my "native" faith tradition.

A sense of what's important: if I learned anything from my evangelical upbringing, it is that my spiritual life matters, and matters profoundly. "Casual," "optional," "complacent," "lukewarm" — these aren't words I grew up associating with faith. Because I was surrounded by people who took discipleship seriously, I understood early on that my religious beliefs and practices have consequences. I learned to invest in the "big questions" (Where do I come from? What is my purpose? Who is God? How then should I live?), because I was taught that such investment makes for a more centered and meaningful life. I was still a tiny human when I learned to prioritize faith. Not a bad way to grow up.

A love affair with the Bible: 66 books, written over 1500 years. 39 in the Old Testament, 27 in the New. Longest Chapter? Psalm 119. Shortest verse? John 11:35. Number of Gospels? Four. Number of Epistles? Twenty-one. Major Prophets? Five. Minor? Twelve. First phrase? "In the beginning." Last word? "Amen." And that's just the easy stuff.

Trivia (and joking) aside, I owe my long and tumultuous love affair with the Bible to evangelicalism. It's in the evangelical church that I first learned to engage with Scripture — to study it, memorize it, apply it, and trust it. From the time I was very little, I understood that "God's Word" is a treasure trove, a book to take seriously for its wisdom, truthfulness, and beauty. By extension, I also came to understand that words — poems, letters, proverbs, stories — matter to God. That he communicates through them in myriad and surprising ways, and that he delights in me when I use my own words to communicate back.

|

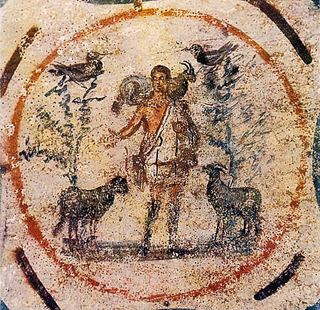

Jesus the Good Shepherd, the Catacomb of Priscilla, 250-300 AD. |

A God who is personal: Not all faith traditions — even Christian ones — emphasize the relational and the experiential. Evangelicalism does. While its institutions, sacred spaces, and clerical hierarchies matter, what matters most is the individual relationship between God and believer. It was no small thing for me to learn, as a child, that the King of the Universe cherishes my heart and mind. Or that Jesus longs to know my particular thoughts, hopes, and desires. Indeed, I suspect now that if I hadn't experienced God in such personal terms during my formative years, I might have walked away from him altogether when aspects of evangelicalism began to bother me. After all, it's much easier to abandon an institution than it is to abandon a Friend, a Father, a Counselor, a Savior. Evangelicalism is all about relationship — and the relationship is still what saves me.

A fruitful scepticism: This is ironic, but evangelicalism injected a healthy skepticism into the very heart of my formation. How? I was raised to be wary of all faith traditions other than my own. Always on guard against heresy and "false teaching," I learned early on to ask hard questions, "test the spirits," and take nothing for granted in the realm of religious life. Of course, no one (and least of all I) knew I'd eventually turn these critical tools against my own tradition. But the tools were right there, all along.

Faith, hope, and love — these three: 1 Corinthians 13, "The Love Chapter," is one of the many I had to memorize in Sunday School, and I still love the trifecta that ends it. Faith, hope, and love. Faith in God and in Christ. Hope for this life and for the life to come. Love beyond measure for all who desire it. I'm thankful to my evangelical upbringing for insisting on these three.

In his book Whistling in the Dark, Frederick Buechner describes Lent as a journey Christians take in the footsteps of Jesus: "Jesus went off alone into the wilderness where he spent forty days asking himself the question what it meant to be Jesus. During Lent, Christians are supposed to ask one way or another what it means to be themselves."

This year, part of my Lenten commitment is to consider Buechner's question: what will it mean to "be myself" as I move from one expression of Christianity to another? The move takes me deep into the wilderness, a place of uncertainty, mourning, trouble, shadow. I don't know yet who I'll become, or where my journey will end. But I do know that I'm not empty-handed as I explore this difficult landscape. I have been given so much — so much that matters, so much that endures.

One of the "graces" I put into those boxes at church reads thus: "For what I am about to receive, may the Lord make me truly grateful."

Yes.

But also this: For all that I have already received, may the Lord keep me truly grateful. Now and always.

YES.

Image credits: (1) Wikipedia.org.