For the weekly Eucharist at my Episcopal church, we leave our pews and gather around the altar at the front. We begin by giving pride of place to our children, literally and liturgically, by placing them at the innermost center of our circle. We then sing a short chorus that's a marvelous summary of the Christian message: "God welcomes all, / strangers and friends. / His love is strong, / And it never ends."

To welcome a child, said Jesus, is to welcome him. And to imitate a child is to enter his kingdom. So at the start of our Eucharist, with the help of our children, we confess this fundamental and non-negotiable truth — God welcomes all. Full stop. There are no qualifications, exceptions or exclusions.

|

|

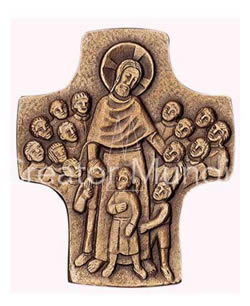

Who's the Greatest? by SZ Richardson.

|

God welcomes all. How could it be otherwise? Why would we ever think differently? This Divine Welcome is the sum and substance of our faith. God's call is to accept that we are accepted.

When the disciples asked Jesus to teach them to pray, he told them that God is like a protective Father. Jesus never prayed to an "almighty" God. He prayed to a welcoming father.

In an affirmation of God's tender care for every person and for all the world, Paul says that we don't relate to God as a slave who fears a master, but as a child who feels safe with a father: "Abba, Father" (Romans 8:15, Galatians 4:6). Abba is the Aramaic word used by Jesus himself that means something like "Pappa." The word is used only three times in the New Testament and conveys a shocking sense of human intimacy with the divine infinite. It's a word that little children first learning to speak used for their father, and that Jesus used when he prayed to God in Mark 14:36.

|

|

Christ sets a child before the disciples.

|

Paul insists that God the father welcomes every person without exception. He makes a clever phonetic play on words in Ephesians: God is the patera of every patria — the father (patera) from whom every family (patria) derives its name. God isn't the God of Jews alone, or the private possession of Christians. He's the father of all fatherhood, the father of every family, or the father of the whole human family. In fact, says Paul, he's the father of "every family in heaven and on earth." We are one human family with a divine Father who welcomes all his children.

As for Jesus, whereas in Matthew he is the son of Abraham and the King of the Jews, in Luke (the only Gentile writer in the Bible), he is the son of Adam. Luke traces the genealogy of Jesus back not just to the first patriarch Abraham, as Matthew does, but to the first human being Adam. And so, at the end of Luke's genealogy, Jesus is ultimately "the son of Adam, the son of God."

Luke thus takes us all the way back to the original creation story, where there is obvious and delightful wordplay in the original Hebrew text. The first human Adam was created from the adamah, from the dust, dirt, earth, or ground. And so just as God is the Father of every human family, Jesus is the son of Adam who recapitulates or represents in himself the entire history of humanity that began with Adam. Everyone is included, no one is excluded. We are all children of Adam.

|

|

Let the Children Come to Me, Benedictine Abbey of Maria Laach, Germany.

|

And God the Spirit? In the Genesis story the stuff of creation was a formless or unformed waste. A shapeless, futile, and empty void. Darkness and desolation covered the watery deep. Things were chaotic. But then a "great wind," the ruach elohim, blew over the waters. The simplest way to read this is a "strong and stormy wind," but translators have never been able to resist interpreting the ruach elohim as the wind, breath, or Spirit of the living God, the literal breath of each and every life. Every breath that I take, each beat of my heart, is a gift of God's Spirit.

Like a tender Mother, the Spirit lovingly hovers, broods, or "flutters" over the watery chaos. This verb "to flutter" (rachaph) is used only two other times in the Hebrew Old Testament. In Deuteronomy 32:11, God says that when he found his people in a "howling wasteland," he shielded, protected, and guarded them, "like an eagle that stirs up its nest and hovers over its young." And in the Greek New Testament, the Spirit is our paraclete — our advocate, counselor and defender who comes along side of us to help, protect, encourage and comfort us.

You might live outside the church or the Christian faith, but no person lives outside the maternal care of the Spirit. That's impossible. The Spirit of God broods, blows and breathes over every life and all creation. And as with the original creation of the entire cosmos, so now with the recreation of our own lives. The Spirit of God forms the formless. He breathes spirit into matter. He creates purpose, order, and meaning out of my chaos. He fills our empty voids with beauty and goodness. He turns darkness into light, night into day, the evening into the morning. He calls those things that don't exist into existence.

The Comforter has come — everywhere, always, for all.

|

|

Jesus blesses the children.

|

In the fall of 2003, I spent two weeks in Oxford for some research and writing. One Sunday morning I walked down to Saint Aldates Church on Pembroke Street in the center of town. No one knows for sure who Saint Aldates was, but the church's first rector, Reginald, started serving the church in 1226. As I walked into St. Aldates, the usher enthusiastically greeted me, “We welcome all sinners!"

I've never forgotten that moment sixteen years ago. The usher couldn't have known it, but his succinct summary of our Christian confession were words that I needed to hear at that time and place in my life: that God the Father, Son, and Spirit welcomes me, always and forever, just as I am.

Dan Clendenin: dan@journeywithjesus.net

Image credits: (1) Sandra Zeiset Richardson; (2) Biblical Art on the WWW; (3) Creator Mundi; and (4) Jesus 8880.